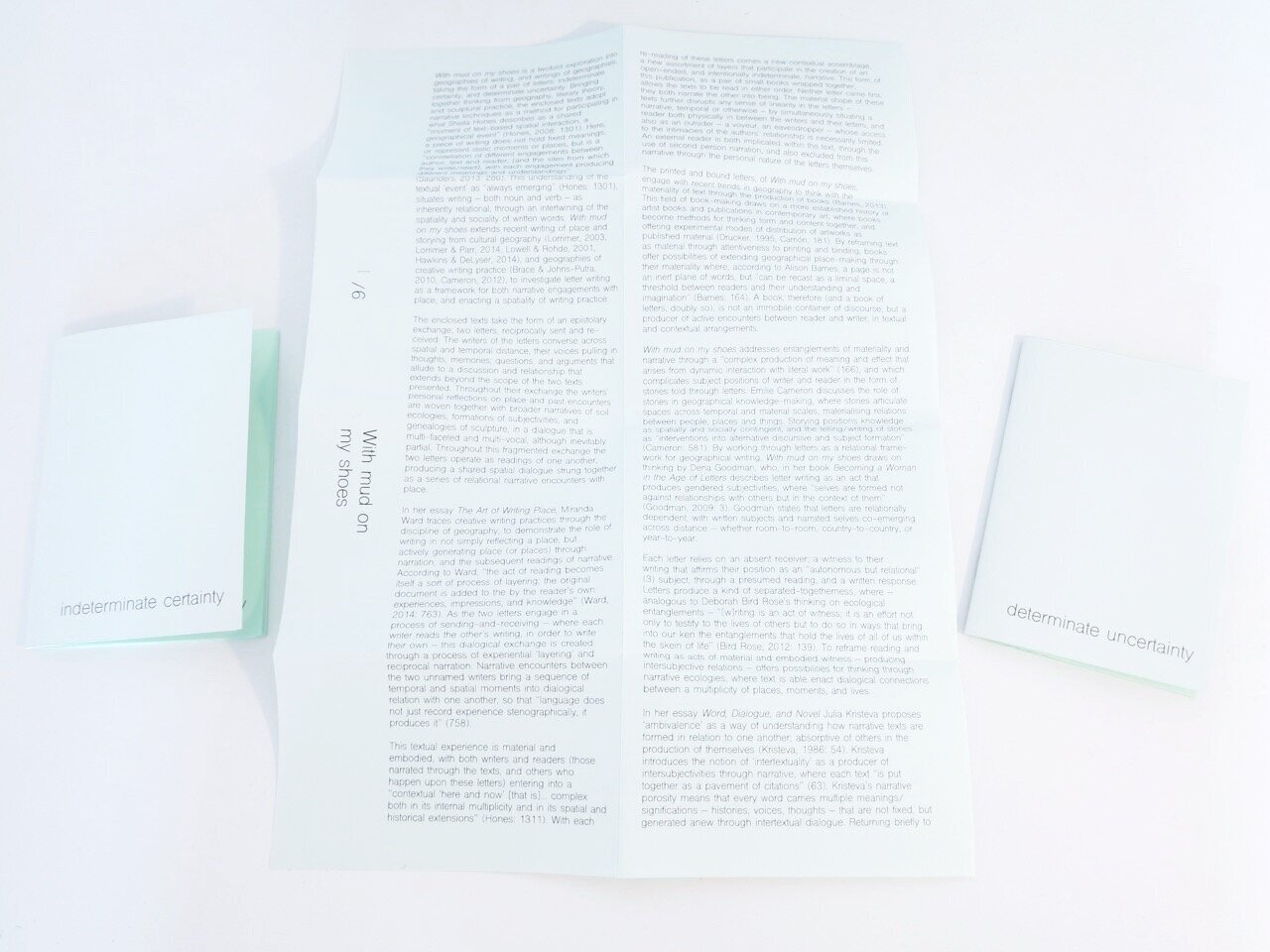

With mud on my shoes

With mud on my shoes (2020)

Dearest ____________,

I have been meaning to write for a while now, but “ambivalence” (Kristeva, 1986: 47) prevented me from doing so. I’ve composed the opening lines to this letter many times, using the words of others in an attempt express myself, and getting lost in a knot of voices. I write to you now with a degree of “indeterminate certainty” (Smithson, 1972: 153), accepting the inevitability of the wrong words. I do so across spatial and temporal distance, unable to predict your response, but anticipating the way my pages will become creased by your thumb and forefingers as you flick through them with impatience. As ever, I find your frenetic speed frustrating, and whilst I sympathise with your refusal to define the terms of our correspondence, I can’t say I agree. If the past is dead and buried, where does that leave us? Now “I write because I do not want the words I find: by subtraction” (Barthes, 1975: 40). This subtraction is like a drifting surface. An interment, where previous encounters meet – in a new form, expressed otherwise. To bury isn’t so much a material metaphor, as an activity that both divides and binds us; “togetherness also involves separating” (Abrahamsson & Bertoni, 2014: 138).

Separating like a wall. Separating like a fence, a boundary, a border, an edge. Separating like a time that can’t be returned to, like a deleted file, or a banal memory, or a sense. Separating like the horizon that shrinks and expands as the terrain changes, and my brother sits in the passenger seat reading crime novels aloud to my mum as she drives. My sister was too young to read whole passages, and I was too fidgety. Each drive takes hours. Days. The horizon reaches out to touch us. The ground shifts from salty and hard, to a dark soil under my fingernails, to a reddish-brown dust that coats the car. Burying is the overlaying of one ecology onto another: a blanketing of dirt and time that we move through. This “time is not a given, it is not that we have or do not have time, but that we make it” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2015: 4). And here, making is a kind of sedimentation, formed in “the fleshy and dirty world of practices” (Abrahamsson & Bertoni: 145). Burying isn’t forgetting – I need you to understand this – but the facilitated contact between layers of memory.

Trying to return to our last encounter, my bodily recall is made slippery by the present. Each letter buries the one before, and now you and I are faced with the task of navigating a temporal build up of past exchange. “The language I speak within myself is not of my time” (Barthes: 39). Our endlessly circular letters don’t produce one point of connection, but a “series of points,” (Smithson: 153) where our contact becomes multiple, and where this dialogue pulls in to it a necessary return. “How does one return? To a country, to a place of birth? To a location that reeks of remembered sensations? But what are these sensations?” (Green, 1997: 39). And what sensorial configurations might this return offer? We make sense, as we make time – as a breakdown of boundaries through a process of burying. “Still, this muddying of boundaries is not a flattening, nor is it easy. It takes work, and it can always produce friction, and lead to failure” (Abrahamsson & Bertoni: 140). Each reply is erosive, and every response requires trudging through the slack of memories our letters have accrued.

About six hours drive north of the salty coast where I was born, weatherboard houses with wrap-around verandahs cluster where two rivers meet. Fruit farms – wedged between deserts – pull water out of the disappearing rivers, and patches of lawn keep the dust down. My dad grew up on a sultana grape farm near here. He was a gun-picker.[1] Planes of sandy soil were carried from further inland by glaciers during the last Ice Age, then deposited and flattened. Most days, sand slows time down. Trees pace themselves along the parched riverbanks. Loose earth drags on your feet, and each step becomes thicker and more determined. People draw their vowels out, letting them hang in the dry air.

The ground here “operates simultaneously in the realms of ecology and of economics, each of which marks time by different clocks” (Puig de la Bellacasa: 7). Irrigated water supports the farms, but dries the rivers. Root systems of watered crops reach down and stabilise the dirt, fixing it in place when the winds come. As the rivers fade, roots become shallower, and the earth begins to drift, “disrupt[ing] the temporality of productionist soil care” (2). From the far west, a large pressure trough can move over the land and pick up topsoil, loosened by the drought. Winds peel back the ground like a blanket. “[I]t does not depend on a logic of understanding and on sensation; it is a drift, something both revolutionary and asocial, and it cannot be taken over by any collectivity, any mentality, any idiolect” (Barthes: 23). The sky goes dark and the horizon disappears.

Earth coats each house in a thin film. A particulating followed by a burying, as an “enactment of alternative and/or marginalized temporalities” (Puig de la Bellacasa: 2), where overproduction of the land leads to a dematerialised skyline and a shuffling of timescales. In response to agricultural acceleration the ground pushes back, removing the wedge of farmland between deserts – or at least blocking it out for a little while. A “disarticulation [that] may lead to the [re]articulation of other histories and other geographies” (MacDonald, 2013: 479). Soil rises into the air and is suspended as an onslaught of particles, creeping over the town and forcing everyone indoors. A wall of dust so thick you can’t breath, it settles momentarily and unevenly, before being inhaled, brushed away, wiped back, and redistributed. The dust storm is a rearranging of earth and a mobilising of horizons. It doesn’t narrate itself in a straight line, it’s a spatial utterance that spreads, deterritorialises, and breaks down spatial and temporal delineations. It’s a layering that isn’t neat, or contained. It’s shapeless and raspy. Surfaces surpass surfaces, disintegrating into one another in a dialogical and vaporous cloud.

I want to ask you about trophic cascades,[2] where the manifestation of an asymmetrical relationship trickles through an ecosystem. It’s the indirect result of an absent body. It’s the tangential connection between a dingo and a grain of sand. “A body’s affects – its capacities for action and relation – are indeterminate, in part, because these capacities are constantly changing” (Lim, 2007: 55). North of where the red dust landed on our car, a fence extends all the way to the sea in the west, and up to the bush in the east. It’s 5,614km long. I’ve lived my whole life south of that fence. The stretched cyclone wire designates an arbitrary inside and outside. It halts the movement of dingoes, and enables the movement of earth. Dry dust blows south through the gaps, settling on dunes. The fence stunts growth on one side and proliferates it on the other. In the absence of dingoes, more foxes, fewer mice, more seed, a spread of vegetation, and deeper roots hold grains of sand together. Dust ignores the fence, but gathers because of it. The dunes shrink in the north, and grow in the south. “They change because they are the outcome of the interactions and encounters the body has with other bodies” (55). Not predetermined, not “prophetic” (Green, 1997: 44), but a slow movement of earth across a designated border.

Far from estrangement, the fence produces two sides that create one another through their separated-togetherness. The fence hosts “events over a certain threshold… switch[ing] non-active dunes… into an active state” (Lyons, Mills, Gordon & Letnic, 2018: 2). They produce their own difference, their own other. The fence’s outside and inside enter into an ecological dialogue of opposition. “Herein lies the paradox of correspondence… that one addresses the other to find oneself” (Goodman, 2009: 3). And this self isn’t singular, but pooled together by connections across multiple bodies and many times. Each dune is an asymmetrical reflection of its pair on the opposite side. “In the light of a unique and unrepeatable identity – irremediably exposed and contingent – the other is therefore a necessary presence… always a co-appearance. Appearing to each other… they reciprocally appear as an other” (Cavarero, 1997: 83).

Our epistolary exchange operates by way of the same separated-togetherness as the mirrored dunes. The words I write to you gather like grains of sand, relativised by the reading of your letters, and the writing of my own. We write at the intersection of “both sequential and synchronous temporal patterns, and the interface of embodied time knots” (Bird Rose, 2012: 128). We write our own trophic cascade; an overflow of affect that situates you opposite me, as my non-identical reflection. You and I write one another into being; “a being-in-relation and a being-in-flux” (Martinis Roe, 2017: 223). We “co-evolve… shaped [by] desire” (Bird Rose: 136) and words, where “writing reads another writing, reads itself and constructs itself through a process of destructive genesis” (Kristeva, 1986: 72). We – you/I – might call this collapse.

It’s an intimate dissolve predicated on difference, “an account of alterity which does not reduce the Other to the Same” (Jones, 2000: 272), but rather multiplies me in relation to you to produce a kind of entropic we. “It’s a story of desire,” (Bird Rose: 134) where “we do not love… in the sense of a comfortable love, a passion that is easy and does not make demands on us… it is a love that is about asymmetric relations, about profound differences, about irreducible otherness… a love that is dirtier and not easy” (Abrahamsson & Bertoni: 141). Through letters you and I narrate our own collapse, a complicated layering, and a convolution of edges: an active burial of text and memories, in which our written relationship deteriorates in a haze of differentiation. “For the text, nothing is gratuitous except its own destruction” (Barthes: 24). And this destruction is something you and I both produce and share, a relational exchange where the written “presence of both [our] temporalities heightens an awareness of the continuous physical presence of entropy; it is not just a hypothetical concept or a fixed image” (Reynolds, 2004: 197). We dissolve into each other through an intimate narration.

Until next time, love for now,

____________ x

[1] A gun-picker is the fastest and neatest at picking fruit on a farm.

[2] Trophic cascade is the term used to describe trickle down effects of the presence or absence on an apex predator within an ecosystem, tracing a relationship between species habitat and geomorphology.